Non-Touch Gesture Interaction: A Usability, Accessibility and Inclusive Design Review

From the dawn of the Nintendo Wii, I’ve had the opportunity to interact with a number of non-touch gesture interfaces. At 7 years old, I held a Wii remote in my hand for the first time and got to experience a virtual interaction just by moving my body.

Although the Wii Remote had some touch features (i.e. you sometimes needed to press the buttons on the remote to accomplish certain tasks), a lot of games could be played simply by the movements of your arm, wrist, and body as you held the remote in hand — from swinging a tennis racket to chopping vegetables to playing an instrument. It allowed for people, especially children and teens, to enjoy playing video games in a way that moved their bodies and kept them active, while adding an entirely new immersive gameplay in the process. Instead of simply pressing a button to hit a baseball, for example, users could now stand up, angle themselves as if they were actually up to bat, and swing their arms to give them a near realistic experience of hitting a baseball.

A few years later, the Xbox Kinect came out. This was the first fully hands free gesture interface I had ever gotten to interact with. Unlike the Wii, where even if you were moving your whole body the system was really only tracking the remote, the Kinect truly tracked every movement you made with your body, from head to toe. With this, I was able to really immerse myself into the games I was playing. If I jumped, my character would jump, and if I leaned one way, my character would lean that way. Navigation was also very unique; for the first time I was able to point my hand and “grab” an item on the screen to move it.

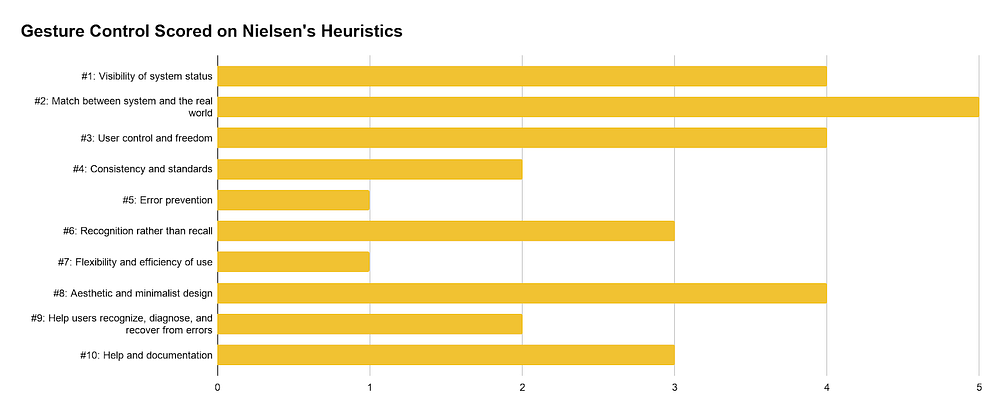

Today, we see gesture interactions integrated more and more into society. We see it with VR, certain cars, and even in ways we might not think about, like using an automatic sink or paper towel dispenser in a public restroom. As smart mirrors gain popularity, we also see how it may soon become more of a staple in our everyday lives. With it’s growing prevalence, let’s take a look at how non-touch gesture interfaces shape up to Nielsen’s 10 Usability Heuristics.

Usability

#1: Visibility of system status

For gesture control, system status can sometimes look a little different then users may be used to. The “system status” may ultimately come from whatever the result of your gesture is (i.e. an automatic sink is on when your hands are under it and the water is running, but off when you move them away). For more visual systems, it could just be a status listed in the top corner of a screen.

#2: Match between system and the real world

Non-touch gesture interactions come as close as possible to matching between system and real world. Because of the nature of gesture control, a lot of users movements mimic real world interactions. For example, the movement you make to jump and hit a volleyball in real life matches the exact movement you would make when trying to do the same using a gesture control system like Kinect.

#3: User control and freedom

Similar to a more visual interface with an undo button, gesture control often has relatively easy methods for undo. Whether it be a swipe or two of the hand or simply stopping any motion at all, with the right program, gesture control can offer just as easy a way back as existing UIs.

#4: Consistency and standards

Because gesture control is such a newly emerging technology, there is little in terms of consistency and standards. Each gesture control technology you run into may function differently, and until gesture interactions are more widely integrated into our lives, this consistency may continue to lack.

#5: Error prevention

The nature of gesture interactions can be very error prone. In my experiences, there is little to prevent a user from making an accidental movement that would then cause an event to occur. For example, if I’m playing a game that involves swinging something in my hand and I happen to have an itch on my head, I either can’t scratch that itch or I scratch it and accidentally swing at something in the game.

#6: Recognition rather than recall

A downfall of gesture control is that sometimes there isn’t a screen or voice associated with the interaction to remind the user how things are accomplished. The upside is that most interactions are rather intuitive. For example, as a driver you need to keep your eyes on the road. In the video below, you can turn up or down the volume in the car by spinning your finger in a circle, similar to how the volume knob turns in a traditional car. This allows the user to keep their eyes on the road while controlling the volume.

#7: Flexibility and efficiency of use

In my experience, gesture interfaces often lack in what customization they allow. This is in large part due to how new they are and how they are still being incorporated into more products. I have yet to encounter a gesture interface that allows customization, but I believe this will be a big trend in the near future in order to allow for accessibility and inclusion.

#8: Aesthetic and minimalist design

Inherently, gesture interactions have a limit since there is only so many gestures a human body can make. In turn, this means most gesture interactions revolve around a minimalist design. The gestures used are often simple, intuitive, and only include just what the user needs to interact. This helps keep users focused and avoids overwhelming them.

#9: Help users recognize, diagnose, and recover from errors

A problem I’ve encountered with the Xbox Kinect and Wii specifically is that if the system is not responding to your gestures there is often no acknowledgement or explanation why. I find myself just turning the whole system off and back on again in hopes of it working, but including an error message that explained the problem would prevent users like me from the frustration of having to leave the whole game.

#10: Help and documentation

Similar to the last heuristic, I find that if my gestures are not being picked up it can be hard to solve and I haven’t personally found much documentation to aid that. However, on another note, most systems do offer some help/documentation that users can refer to when they forget or need to learn new gestures.

Compared to Nielsen’s 10 Heuristics, the overall usability of gesture control is fair, but there is room for improvement as it develops. Next we’ll take a look at how gesture control stacks up in terms of accessibility by comparing certain interactions with it to some of the main principles of accessibility.

Accessibility

One of the largest groups of people who may struggle with gesture control is those who have motor disabilities. Motor disabilities may result in a lack of movement, limited movements, or a lack of muscular control that may cause involuntary movements. This can even include people who are missing limbs. When looking at the 4 main principles of accessibility, this means there is a lot to account for in terms of operability.

For example, the above gif shows a man using Microsoft’s new gesture tracking system created as part of their Project Gesture initiative. This technology may look great to the average user, but presents clear problems for those who struggle with motor disabilities. This system uses very precise movements of the hands and fingers that not everyone may be able to accomplish. A motor disability can keep someone from being able to move their fingers this precisely, if at all, or the motions may be erratic and not understood by the system. For a non-touch gesture interface to be operable for all users, it should be sure to include customization. A user with a motor disability should be able to customize the interface in order to work with gestures that the user finds simple and is capable of, even if that is different from other users.

Similarly, users with cognitive disabilities should also be accounted for when designing non-touch gesture interfaces. Some main limiting elements include a lack of memory, lack of attention, lack of problem solving abilities, and more. For gesture interactions to be accessible, they must be understandable to all.

To enhance understandability, having clear help and documentation as well as directions on screen as often as possible are important. Where the average user might remember all the gestures needed to navigate a system, a user with a cognitive disability may not. Having an option to put gesture directions on screen or even an option to speak instead when a user cannot remember a gesture could greatly enhance their user experience.

For example, in the above video, a user navigates through an example of a gesture controlled Netflix application. Adding a simple line that reads “swipe hand left and right to navigate” or, even better, a small visual of a hand swiping left and right at the bottom could really help users who struggle with certain cognitive disabilities remember and easily navigate the app.

Overall, providing clear help and direction can make gesture interactions much more understandable for all. Next, we’ll take a look at non-touch gesture interactions as they relate to inclusivity.

Inclusivity

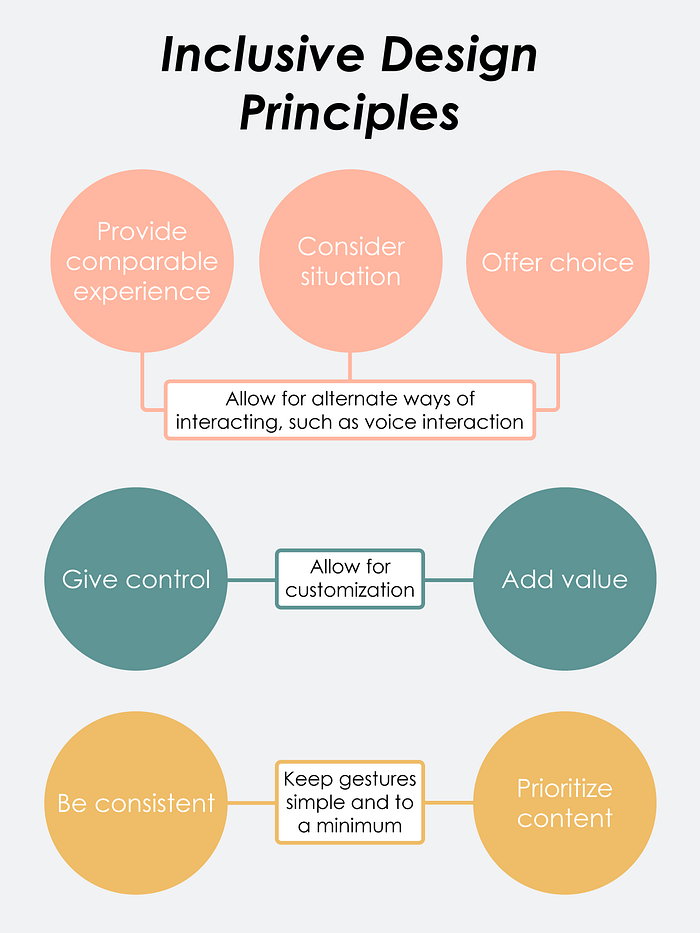

When we look at some of the principles of inclusive design, 3 of the principles tie together for gesture interactions. Designing to provide a comparable experience, considering the situation, and offering choice can all be accounted for in the same way — creating non-touch gesture interfaces that expand beyond just non-touch gestures.

Although interacting with a non-touch gesture interface will work well for most people most of the time, there is times when it will not work. For example, maybe you have a smart mirror that you want to interact with, but you injured yourself in a recent skiing accident and temporarily have a limited range of motion in your arms. This prevents you from performing a number of important gestures needed to interact with the system. Similarly, maybe you have gesture control in your car to control the radio, but the roads are very icy and it’s not safe for you to take your hand off the wheel. How will you change the radio?

For situations like these, it is best to provide alternative modes of interactions when non-touch gesture control is not an option at the time. For example, adding a voice control feature would allow the users to still interact with the system even when they can’t move to make gestures. This provides a comparable experience for the user, considers the situation, and offers the user a choice in how they want to interact, creating inclusivity.

Along these lines, giving control and adding value is also important to inclusivity. Similar to accessibility, this can again be solved by allowing for customization. Customization allows the system to work for the user, as opposed to making the user work for the system. For example, if a user is left handed and using a smart mirror like the one above, they’ll want to be able to customize the interface so that the apps are on the left side closer to their left hand. This makes task completion much easier for the user. They may also want to customize specific gestures so they’re more comfortable for someone left handed, improving their experience.

Lastly, being consistent and prioritizing content are the final keys to inclusivity. Keeping the gestures used to interact with a non-touch gesture interface simple and to a minimum helps with this.

In the above video, we see an example of a gesture controlled interface by Microsoft. The gestures needed to interact are often very simple and are repeated over and over again, such as a pinching, swiping, and grabbing motion. This minimizes the need for a user to remember dozens of various gestures and only what you need is prioritized. By having consistent, priority based gestures, the system is on its way to being more inclusive.

Here’s a summary of the inclusivity principles discussed:

Overall, we’ve learned that non-touch gesture interfaces are an up and coming mode of interaction with technology that, through their uniqueness, will provide many opportunities to enhance usability, accessibility, and inclusivity when done right. Because this technology is so new, it is necessary for designers to keep in mind how important their impact will be on the future of this interface. By creating standards and consistencies that allow for usability, accessibility, and inclusivity now, they can make sure that all future iterations of these interactions keep these areas in mind and support all types of users. Concepts like allowing for customization, using simple gestures and directions, and others mentioned above will allow this emerging tech to flourish by best serving its users.

Sources: